Written by Barbara MacAdam

One of the principal enigmas in judging art is that nothing is as it seems. We dismiss that indefinability at our own risk. Take the idea of the monochrome. The term is defined as a single color with or without variations in tone, much akin to Minimalism, but how do we respond to an artwork when we exclude such properties as line and figure that give clues to subject and meaning?

Left with color alone, which we may all perceive differently, we must wonder what draws us to a monochrome and what inspires an artist to tell so apparently little.

Shirazeh Houshiary, Genesis, 2016. Pigment and pencil on black aquacryl on aluminium. 74 3/4 x 212 5/8 inches. ©Shirazeh Houshiary; Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

Artists Imi Knoebel, Robert Ryman, Marcia Hafif, Rudolf De Crignis, Jill Baroff, and Bosco Sodi offer just a glimpse of the range, power, and expressive potential of monochromatic art. The spectrum is broad, yet the constraints the artists set for themselves are narrow and extreme.

Monochrome purports to offer a neutral base from which to read a painting or sculpture. And as such, it can stand as a starting point for inspiration, a container awaiting filler.

Art historian and critic Barbara Rose has written, “Monochrome art has two origins: the mystical and the concrete.” We see “the object as material presence, not illusion.”

Yves Klein, likened monochrome painting, using mostly his own “International Klein Blue” to “an open window to freedom,” merging the spirituality of intense focus with the obviously material.

Bosco Sodi, Untitled, 2017. Clay cubes. 88 1/4 x 22 1/8 x 22 1/8 inches. ©Bosco Sodi; Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Iranian artist Shirazeh Houshiary, showing now at Lisson Gallery, offers only ostensibly monochrome renderings. Her works have compulsive underpinnings—almost invisible writing that appears as uniform color and is made up of the words of prayers or songs, for example, written repeatedly in cursive, forming waves of tone and intensity. In this way Houshiary conveys feeling, mood, and rhythm, which we perceive almost subliminally.

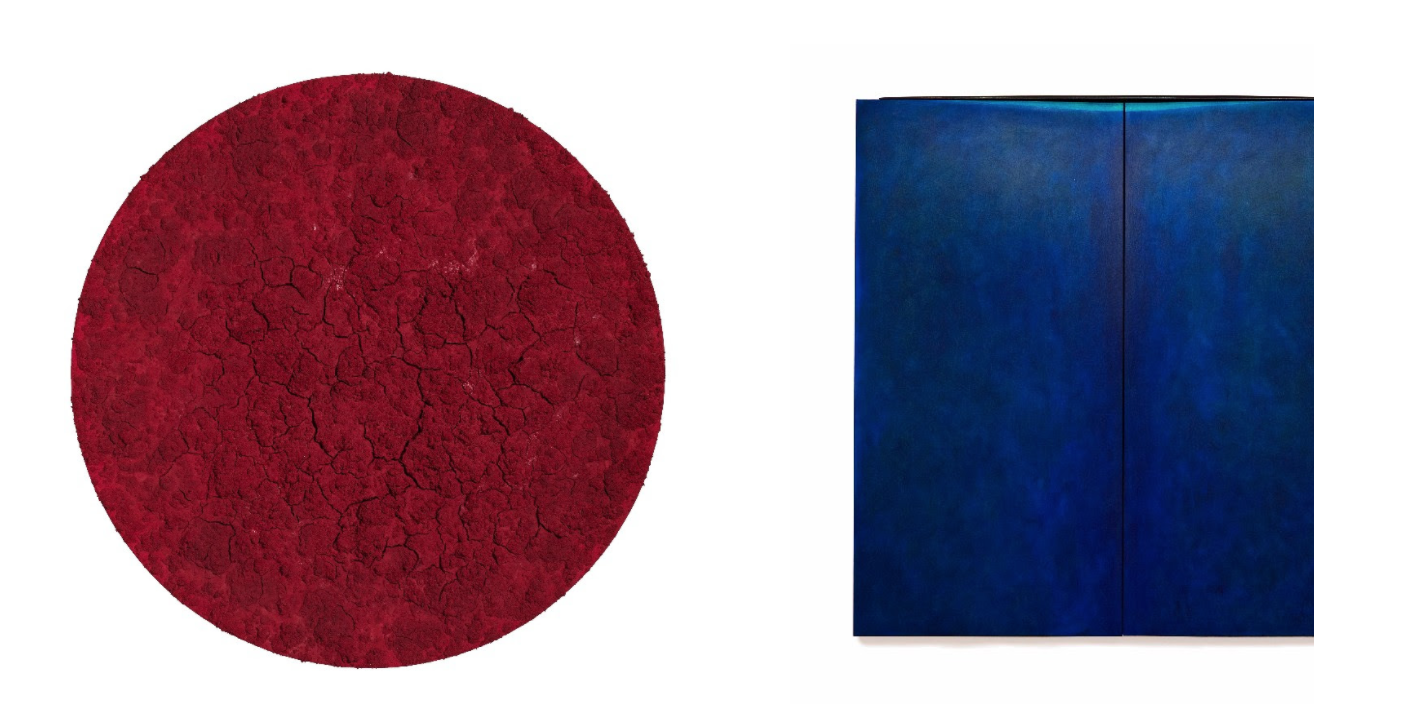

By contrast, much of the impenetrable work of Mexican-born sculptor Bosco Sodi, who is currently the subject of an exhibition at Paul Kasmin gallery, consists of solid enigmatic mounds of textured and intensely colored pigment that could be viewed at most as barren landscapes or deserts, but there are no or clues—just dense substance. His sculptures, stacked cubes in modulated shades, also give barely a clue to personal associations.

Robert Yasuda, a near monochromist, claims to seek total nonobjectivity—which he distinguishes from abstraction, as he explains in a video made at P.S.1 as was reinstalling a site-specific piece he’d made for a show there 50 years ago. An abstraction, is taken from something else, he notes, where as a nonobjective work is free of association (which may or may not be the case, but for argument’s sake, it works.). He tries to get to the point where there can be no specific associations but where the work may convey instead “feelings, optics, or the way your eye operates in delighting in color.”

Yasuda notes how some people may look at his work and say there’s nothing there, but the truth for him is that “what is not there ends up being the subject.” And it changes as you move.

Left to Right: Bosco Sodi, Untitled, 2016. Mixed media on canvas. 73 1/4 x 73 1/4 inches. ©Bosco Sodi; Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery. Robert Yasuda, The Deep, 2017. Acrylic on fabric on wood. 72 x 72 inches. ©Robert Yasuda; Courtesy of Robert Yasuda.

More ostensibly uncompromisingly, the late Rudolf de Crignis would paint so many layers to yield what appears to be a solid blue surface (one that he would always refer to as gray as if to declare a kind of non-referential neutrality and a permanent state of irresolution). His canvases are so stunning with shades shifting so subtly that viewers can’t help being drawn in to wonder what they are viewing. Every atmospheric variant surrounding the image--humidity, fog, sun, shade, glare, breeze, and so on—changes the work itself and so our understanding of it.

One attraction to monochrome, besides what viewers bring to it, is its democracy: it begins in the middle, so to speak, largely without obvious history. It is really up to us to be co-creators. It can be like sitting with an extremely laconic person and finding ourselves uncontrollably filling the seeming void with words and thoughts. But then, finding comfort in inadvertently creating something new.

Robert Wilson, in describing how he conceives a project says, he begins with one point (maybe two), makes a mark, and then lets it open him to an ever larger structure with sections that he may fill or leave empty or black out. That’s what we have to decide: do we stick with one idea or view of a work, or do we build mental constructions that may or may not please us and that may or may not be totally to the point, but just as the artist must begin somewhere, so must the viewer.

- Barbara MacAdam

Please use the "RESPOND TO ISSUE #2" button on the top right of this page to submit your answers.